A Man, a Plan and a Span: Henry Flagler and the Overseas Railroad

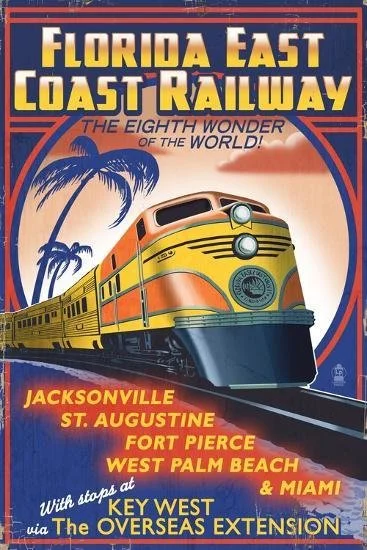

The Key West Extension of the Florida East Coast Railroad was known in its time as “The Eighth Wonder of the World”.

It ranked with the Panama Canal as one of the great engineering projects of the new century; a demonstration of America’s burgeoning confidence, technological ingenuity and “can do” spirit that would soon be further expressed in the creation of other marvels such as the Golden Gate Bridge, Hoover Dam and the Empire State Building.

On a more practical note, the Overseas Railroad directly linked the island boomtown of Key West to Miami and the rest of Florida, and was the culmination of Henry Flagler’s dream of providing reliable and fast transportation throughout the state.

It ranked with the Panama Canal as one of the great engineering projects of the new century; a demonstration of America’s burgeoning confidence, technological ingenuity and “can do” spirit that would soon be further expressed in the creation of other marvels such as the Golden Gate Bridge, Hoover Dam and the Empire State Building.

On a more practical note, the Overseas Railroad directly linked the island boomtown of Key West to Miami and the rest of Florida, and was the culmination of Henry Flagler’s dream of providing reliable and fast transportation throughout the state.

A Dream Awakens

If anyone could see such an enormous project through to completion, it was Henry Morrison Flagler. Born the son of a minister from Hopewell, New York in 1830, Flagler was a man of profound determination and vision who had risen to prominence as John D. Rockefeller’s right-hand man in the company that would become Standard Oil.

By the early 1870s Standard Oil was America’s leading oil producer and its principals were looking to invest their newly made millions in other business ventures. In 1878, Flagler found himself in Florida seeking refuge and respite from a typically harsh New York winter. Flagler saw in south Florida’s swaying palms and pristine beaches a virtual paradise that needed only sufficient infrastructure to reach its full potential.

Henry Flagler was the kind of man who was blessed with the gift of being able to see the big picture. This talent served him well at Standard Oil where he oversaw the establishment of the many supporting industries needed to facilitate the flow of oil from the company’s fields. One of these essential cogs was the railroad, without which oil could not be transported to refineries - these being the days before pipelines and modern road networks.

As Flagler enjoyed his honeymoon with his new wife Ida in St. Augustine, Florida, he could see that an efficient railroad network and upgraded visitor accommodations were crucial to Florida’s success as a vacation paradise.

Flushed with excitement and buoyed with optimism, Flagler resigned his position at Standard Oil and systematically began to turn his dream into reality.

Big plans require deep pockets, and Henry Flagler’s pockets were very deep indeed, thanks to his stint at Standard Oil. After moving his household to St. Augustine and buying several hotels there, he set about upgrading them to the level of the very best French Riviera resorts. It was here that he ran into another problem: building supplies and materials were only trickling into St. Augustine on Florida’s rudimentary railway system.

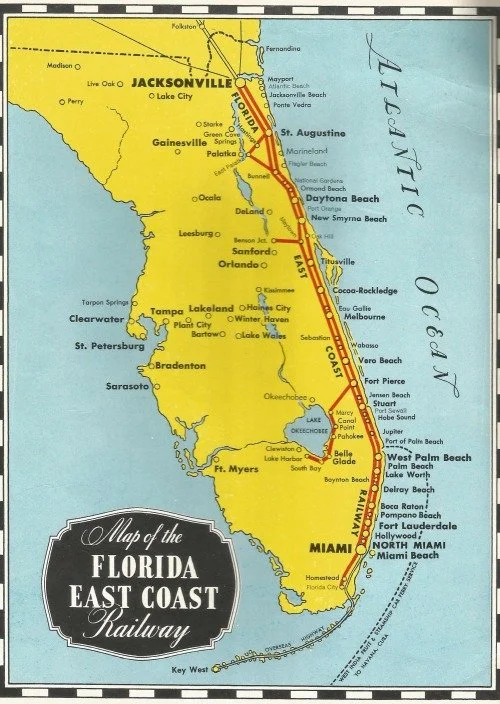

Once again Flagler dug deep, this time purchasing the Jacksonville, St. Augustine & Halifax River Railway; the St. John's Railway; the St. Augustine and Palatka Railway and the St. Johns and Halifax River Railway. By 1889 these various lines had been linked and consolidated, providing travelers and businesses with a reliable rail link from Jacksonville in the north to Daytona in the south.

Flagler built stations, depots, hotels and even churches and hospitals along the route that became the nuclei of new towns like Titusville and West Palm Beach. By 1895 the “Florida East Coast Railway Company - Flagler System” (known as the “FEC” for short) was officially incorporated.

Rolling South, and Beyond

The seeds Flagler had planted were beginning to bear fruit as the 19th century drew to a close. Palm Beach boasted glittering resort palaces like The Breakers Hotel and the Royal Poinciana Hotel that attracted high rollers, captains of industry and the “jet setters” of the day from either coast and from across the Atlantic.

Florida’s building boom shifted into high gear and Flagler was no longer alone in his efforts to improve the Sunshine State’s attractions and infrastructure. In response to interest from landowners and investors in the southernmost part of the state, the FEC continued to extend its rails southward, reaching the frost-free shores of Biscayne Bay by 1896.

Flagler saw in the unincorporated land at the line’s terminus an enticing opportunity to build a residential, entertainment and industrial center that would act as an economic engine for the entire southern part of the state.

As before, Flagler got the ball rolling by improving the harbor, laying down electric, water and sewer lines beneath brand new streets, even subsidizing the new town’s first newspaper. It was fitting that the new town should bear the name of the man responsible for its establishment but Flagler was modest to a fault.

Instead, he suggested to the town’s 444 inhabitants that they choose “Miami”, the name of a former plantation founded on the south bank of the Miami River. The name was approved and Miami was born.

In the year 1900, Henry Flagler reached his 70th year and could certainly be forgiven for wanting to slow down a little, perhaps to settle down and enjoy his retirement in the state where he was responsible for so much development. Flagler wasn’t your average septuagenarian, though, and even in his old age he could still be inspired into action.

The next spark that set Flagler’s imagination ablaze was president Theodore Roosevelt’s announcement that construction would soon begin on the Panama Canal. This was no small undertaking. A French-sponsored attempt to build a canal through the Isthmus of Panama in the 1880s was abandoned after more than 20,000 workers had perished from yellow fever and malaria. Roosevelt, however, embarked on a disease eradication program he believed that, combined with the latest gasoline-powered construction machinery, would surely achieve success. Flagler saw that disease and technological shortcomings were no longer obstacles to a plan he had been mulling over since the FEC had ceased its southern expansion a decade earlier: an extension of the railroad south past Miami, “island hopping” all the way to Key West.

Spans Across the Ocean

Key West lay 150 miles southwest of Miami at the tip of the long chain of islands and sandbars that extended in a curving arc into the Gulf of Mexico. First discovered by Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon in 1521, the island of Key West was claimed for the United States in 1822 by Matthew Perry. Perry would achieve lasting fame 30 years hence when he led a flotilla of “Black Ships” to force the opening of Japan to American trade. By the end of the century, Key West had become a thriving town of 20,000 with a busy deep-water harbor and an economy based on salt making, marine salvage and cigar manufacturing.

Flagler recognized that a rail connection to Key West would provide profit from the increased trade expected once the Panama Canal was opened to inter-ocean traffic. So it was that in 1905, construction began on a project that seems wildly audacious even from our viewpoint a century later: the Key West Extension of the Florida East Coast Railway. Panned by some as “Flagler’s Folly”, the proposed extension would need to cross the 128 miles between the end of the Florida peninsula and Key West, most of it being the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

Progress was slow but steady with construction pausing occasionally as hurricanes blew through the Keys as they are won’t to do. Thousands of men toiled for over 7 years on the Extension, building a stretch of Italianate bridges and causeways that slowly but surely spanned the wave-tossed distances between the Keys.

Finally in the spring of 1912, the first train from the Florida mainland pulled into the Key West station. Proudly standing on the balcony of the observation car upon arrival was none other than Henry Flagler, who would not have it any other way. Goodbye “Flagler’s Folly”, hello “Eighth Wonder of the World”. Sadly, on May 20th of 1913 at the age of 83, just over a year after completing the greatest of his many triumphs, Henry Flagler died following a fall down the stairs at Whitehall, his Palm Beach estate.

From Triumph to Tragedy

A golden era in train travel ensued as elegantly appointed passenger trains plied the Overseas Railroad to and from America’s new southernmost point. Effusively illustrated FEC advertisements prominently featured the lines signature arching bridges and enticed vacationers with tag lines like “Every Day a June Day, Full of Sunshine - Where Winter Exists in Memory Only”. As Floridians know only too well, unfortunately, Mother Nature can be capricious, especially as those sunny June days fade into the unsettled dog days of August that portend the start of hurricane season…

No less than five hurricanes had struck the Florida Keys during the Extension’s construction, including one particularly vicious storm in 1906 that killed several hundred workers. Everyone involved knew what dark beasts slouched towards the Gulf coast each year as the days began to shorten.

Perhaps a comparison can be made to the designers of the Titanic who were fully aware of the silent mountains of ice the great ship would be expected to encounter in the frigid waters south of Greenland.

They planned for any eventuality by incorporating a system of watertight bulkheads into the Titanic’s hull. The ship could withstand the flooding of four bulkheads, but not the five breached by the iceberg.

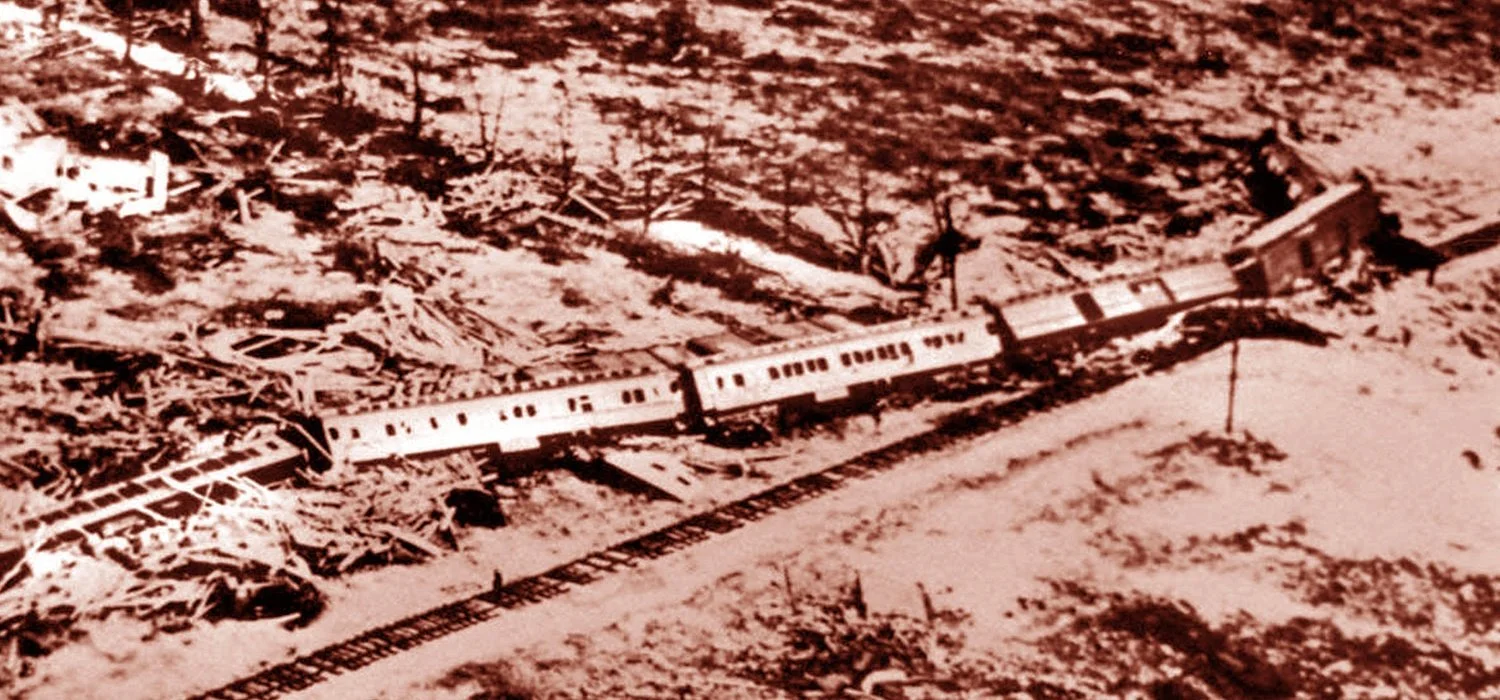

The Key West Extension was built to withstand hurricane-force winds, but the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 was no ordinary hurricane. This was a Category 5 monster. Residents of the Keys had only an inkling of what was coming their way - both hurricane forecasting and radio broadcast news were in their infancy.

Even more oblivious were the more than 350 World War I veterans on Lower Matecumbe Key who had been posted there to build bridges for the WPA (Works Progress Administration). It is difficult to imagine the horrific ordeal suffered by these men as shrieking 160mph winds whipped away their flimsy shelters and blasted beach sand with a force powerful enough to peel skin.

The crowning blow was the 16-foot storm surge that washed away anything not already blown away by the winds, and that included the rescue train sent down the Extension by the FEC from which only the engine remained upright and on the rails.

Among the more than 400 people who perished as a direct result of the storm were 259 veterans. To this day, the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 remains the most powerful cyclone ever to strike the US mainland.

Death and Re-Birth

In the aftermath of “The Storm of the Century”, as it would be come to known, FEC inspectors discovered that some sections of the Overseas Railroad’s causeways were heavily damaged and others were completely destroyed.

The line had suffered from financial woes after the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and could not afford to repair the Extension. The crumbling remnants of the once grand gilded-age showpiece that had cost $40,000,000 to build were sold to the State of Florida for a mere $640,000.

The State immediately set about re-establishing the land link to Key West, but this time it would be roads and not rails that spanned the seas. Many of the Key West Extension’s surviving bridges and causeways were utilized to form the Overseas Highway that opened in 1938. The highway was beginning to show its age by the 1970s and most of it was rebuilt over the following decade.

Driving down US1 to Key West is still an exhilarating experience. One can imagine the excitement (and not a little trepidation) felt by passengers riding the Overseas Railroad in those bygone days.

Looking back at the Key West Extension of the FEC and its catastrophic demise, one must resist the temptation to blame the tragedy on the unbridled optimism so characteristic of the early years of the 20th century.

Again, we can recall the “unsinkable” Titanic (which coincidentally sank in the same year as the Key West Extension was completed), whose watery grave serves today as a monument to mankind’s hubris and a misplaced faith in the infallible power of technology.

Have we learned anything in the 70 years since the Labor Day Hurricane dashed Henry Flagler’s dream to the depths? Perhaps not - hurricanes continue to frustrate the best-laid plans of men and reduce his works to dust. The deadly toll taken by Hurricane Katrina and the flooding of New Orleans show that there are still limits to what humanity can accomplish when faced with the power of nature.

by Steve Levenstein, 2006 ©RLinc