Arms and the Men: How Bankers, Blockade Runners and Bravado supplied the South

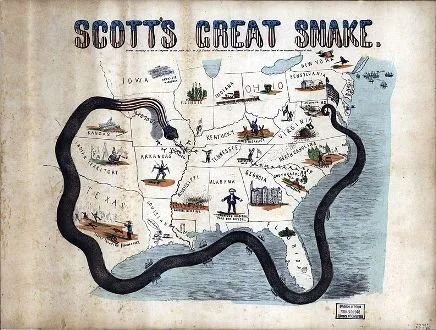

The most simplistic rationale for the defeat of the Confederacy in the Civil War posits that the South's primarily agrarian economy could not provide their armed forces with the tools of modern warfare on the one hand; and that the Union coastal blockade prevented these requirements from being met from abroad.

There is no doubt that the Confederate industrial base was not structured to support a long conflict and naturally their leaders sought out overseas suppliers to fill the procurement gap. Blockade or not, the Confederacy needed arms and ammunition from foreign suppliers on an ongoing basis to prosecute the war. That they were successful beyond all expectations is astonishing, even into the spring of 1865 (and beyond, as we shall see), and a tribute to the efforts of a group of extraordinary men for whom no problem was without a solution.

Quest for Firepower

Judah P. Benjamin was the Attorney General of the CSA at the beginning of the war and was later appointed Secretary of War, then Secretary of State by his old friend Jefferson Davis. Benjamin knew that the CSA's trade with the nations of Europe depended on having freedom of the seas and the ships with which to sail them. He also knew that the Union would do everything in its power to disrupt that trade, and that the ever-tightening blockade of the Confederacy's coastal ports would eventually deprive the South of munitions imports - as well as the cotton exports that were needed to pay for them.

Benjamin was a tireless and energetic man who typically arrived at his office by 8:00am in the morning and often did not leave until 2:00am at night. Ever the optimist, he saw that there were pre-existing conditions and situations that he could exploit to the South's advantage. For one, there was a general feeling in the capitols of Europe that it would benefit their own self-interest if the pre-eminent power in North America remained divided.

Benjamin focused on Great Britain. His overriding priority was to bring the British into the war on the side of the Confederacy, but if that wasn't possible then at least secure their cooperation with and acquiescence to the sourcing and supplying of arms. Benjamin assumed that Britain needed to maintain good relations with the Confederacy in order to assure continuing delivery of the cotton upon which their textile industry depended. On this point, however, he was overly confident.

In 1860, British commodity buyers had availed themselves of a bumper cotton crop and correspondingly low prices - the country was awash with cotton. Even so, there were powerful political factions in Britain who were pro-Confederacy. These were hard-headed businessmen who wanted to secure the cotton supply for years to come, and who also knew that tremendous profits could be made supplying the Confederate (and Union, for the matter) war machine.

The center of pro-Confederate sentiment in Britain was the port of Liverpool. Located on the northwestern coast of England, Liverpool was the main British shipbuilding center and it was also the port where most of the American cotton exports were received. Naturally, the bankers, brokers and financiers who underwrote and facilitated the cotton trade had branches in Liverpool. One of the largest was Fraser, Trenholm and Company.

Headed since 1853 by George A. Trenholm, the company had interests in banking, cotton pressing, hotels, plantations, railroads, steamships and wharves. The company was based in Charleston SC and its Liverpool branch acted as the Confederacy's overseas banker.

"You Can Run" by Tom Freeman - The Confederate Raider C.S.S. Alabama in pursuit of the clipper ship Contest, November 1863

Judah Benjamin, together with Navy Secretary Stephan Mallory, set plans into motion that would exploit and expand the Liverpool Connection. In June of 1861, Capt. James D. Bulloch arrived at the Liverpool offices of Fraser, Trenholm with a mandate to order ships to be built for the Confederate Navy. Fraser, Trenholm backed up Bulloch and gave him the credibility (and the credit) he needed. Bulloch wasted no time in placing orders for state-of-the-art ships such as the CSS Alabama, CSS Florida and CSS Shenandoah.

The Alabama was arguably the most effective commerce raider in maritime history. Captained by Raphael Semmes, the Alabama sent 55 ships to the ocean depths and captured 10 others during a voyage that took her from the Azores to Newfoundland, Brazil to Singapore, and finally to a watery grave just off Cherbourg, France. So effective were the Confederate commerce raiders that insurance rates for Union ships shot up 900%.

The Union's representatives in England, notably Charles Francis Adams (son and grandson of US Presidents' Adams) who was the North's highest ranking diplomat, protested to their British counterparts that the construction of these ships was a violation of their country's neutrality in the conflict. In actual fact, however, it was not: Bulloch arranged for the unarmed but otherwise complete ships to sail to the Azores where they were fitted out as warships and commissioned with Confederate crews delivered by steamship.

Agents of Fortune

George A. Trenholm was a prototype entrepreneur and quite a character in his own right. When he wasn't managing his far-flung financial empire, he was dabbling in politics. Trenholm was very active in social circles and had the ear of many high-level politicians. It's likely that numerous plans were set in motion over drinks served at Ashley Hall, Trenholm's palatial estate in Charleston that was said to have rivaled the Governor's mansion in its opulence. In addition to his shipping and banking empire, Trenholm owned hundreds of choice properties including docks, plantations and fine homes. In today's money, he would be a billionaire.

In recent years, speculation has arisen that Trenholm was the model and inspiration for the Rhett Butler character from Margaret Mitchell's epic "Gone with the Wind". Certainly, there are parallels: Both Trenholm and Butler were wealthy raconteurs and admired philanthropists. Trenholm was described by those who knew him as "tall, brave and handsome, with the sweetest smile of any man". Trenholm and Butler were praised for their efforts to supply the Confederacy with weapons, but also criticized for importing luxury goods and selling them at a spectacular profit.

After the war, both Trenholm and Butler were arrested and nearly executed - but escaped that fate when they threatened to expose their Northern business connections in the arms trade. Yet another curious fact is that Trenholm had a good friend in Richmond by the name of Edmund Rhett. Margaret Mitchell had always claimed that her characters were fictional and not based on any actual personages, and she certainly never admitted any connection between George Trenholm and Rhett Butler.

By the end of the war, Trenholm had built up a fleet of over 60 large oceangoing steamships and dozens more sailing ships that would be the envy of many a sovereign nation. A significant number of those ships were purpose-built at the Liverpool shipyards as cargo carriers by description; blockade runners in fact.

Back in Richmond, Judah Benjamin and the Confederate War Department conspired to place a savvy arms buyer on the ground in England. After all, what was the point in having the best ships that money could buy if they couldn't be loaded with the best arms money could buy? Time was of the essence - there was a war on and armies were on the move. Since the Confederacy could not hope to supply their troops with arms and ammunition on their own and the best infantry rifle in the world at that time was the British P-1853 Enfield, Benjamin arranged for Major Caleb Huse to ship out to Liverpool on a fast steamer and begin buying Enfields in bulk.

Originally from Massachusetts, Huse could trace his ancestry back to a Richard de la Huse who fought with William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. His earliest American ancestor emigrated to Newburyport, Massachusetts in 1635, where Caleb Huse was born in 1831. Huse, a West Point graduate, was in charge of training the Alabama Militia when the Civil War began. He arrived in Liverpool ahead of many Union purchasing agents and set about locking up the market for top-quality Enfields.

Now, there were Enfields and there were Enfields... and Huse was perceptive enough to know the difference. He had been advised that he couldn't deal directly with the British Defence Ministry as that would breach their neutrality, but that he could order, purchase and take delivery directly from of the dozens of suppliers who actually manufactured the arms. Huse would settle for only the very best "Number 1" Enfield rifles. The suppliers had various standards and production methods, but only the London Armoury Company could guarantee delivery of machine-made Enfield rifles with interchangeable parts.

Huse contracted with London Armoury to supply as many rifles as they could make. In fact, ALL of the company's production for 1864 was destined for the Confederacy, and a good portion of their 1865 production as well.

The Union also was very interested in purchasing the Number 1 Enfield from London Armoury, but Union agent Marcellius Hartley was only able to acquire about 2,000 rifles that were overruns on other contracts. Huse and the CSA got the lion's share.

Huse wasn't about to rest on his laurels. In 1863, the Union armies began to receive large quantities of the M-1861 Springfield rifle and cancelled a contract for "Number 2" hand-made Enfields with an arms-making consortium in the English industrial city of Birmingham. Huse immediately swooped in and soon the "Birmingham Small Arms Trade" association was back at work, turning out Enfields for the Confederate Army.

The quality of the BSAT rifles was not as good as the London Armoury guns but by stepping in when he did, Huse acquired badly needed rifles at a reduced price. In his capacity as Arms Buyer for the CSA, Huse did not limit his orders to rifles, nor to England. A short visit to Austria netted him approximately 30-40,000 Austrian "Lorenz" rifles, along with artillery pieces of various sizes.

Signed, Sealed, Delivered

With Bulloch arranging the shipping, Huse sourcing the arms and Trenholm paying the bills, all that was left was getting the goods safely into the Confederacy. Once again, Fraser, Trenholm and Co. proved that money can grease the squeakiest wheel. British contractors were paid to carry cargo for the CSA from England to any number of British ports in the Caribbean. Bermuda was also a popular destination.

Once in port, the cargo would be transferred to many small, fast Confederate blockade runners who would then attempt to run the Union blockade. This was a relatively simple undertaking, even into 1863. When the war began, the Union Navy only comprised some 90-odd ships and perhaps only two dozen of those were fit for blockade duty. Divide 3,500 miles of coastline by 24 and... blockade running was being done by most any vessel that could float.

Eventually though, the blockading fleet grew to several hundred ships and their crews became quite skilled at intercepting smugglers. To adapt to these changing conditions, blockade runners took to painting their ships light gray or blue-green, cutting down the masts, and flying whichever flag of convenience was convenient at the time.

Banshee II - Pride of the Anglo-Confederate Trading Company, launched in the summer of 1864

One of the most renowned of the Confederate blockade runners was Thomas Lockwood. Born in Wilmington NC in 1831 (the same year of birth as Caleb Huse), Lockwood was a born seaman who made his reputation captaining the Carolina, a side-wheel steam packet owned by Fraser, Trenholm and Company. Lockwood moved to Charleston to marry in 1860 and set up house on land he purchased from his employer.

In the summer of 1861, Lockwood was given command of the armed privateer Theodora and began his legendary career as a blockade runner. On one of his trips to Havana, he returned to Charleston with a load of supplies that included 200,000 Cuban cigars.

By 1862, Lockwood had firmly established himself as one of the most skilled and successful blockade runners and he was often called upon when sensitive or crucial cargoes needed to be run past the blockade.

He delivered shipments of gold to Britain and once smuggled in a complete engine for an ironclad. Perhaps his greatest triumph was his landing of a huge cargo of supplies and gunpowder right before the battle of Shiloh. It was said that every wagon in town was used to load the provisions onto a train that brought them to General Johnson's encamped army.

It's estimated that Lockwood made up to 40 successful runs through the blockade through the end of 1862 when his ship "Kate" sank in the Cape Fear River with a million-dollar cargo on board. Lockwood survived and the Kate's cargo was salvaged. He continued without a pause, on the "Elizabeth" this time, until the ship ran aground on a sandbar off the North Carolina barrier islands in late 1863.

As Lockwood's activities had earned millions of dollars for Fraser, Trenholm and Co., his appreciative employers sent him to Liverpool where he placed orders for two new massive and speedy cargo ships, one of which he was to be given command of as soon as she was commissioned. By October of 1864, the ships were ready. Lockwood had spent over 50,000 English pounds of Fraser, Trenholm's money on his ship, christened the "Col. Lamb" by Lockwood's wife. Lockwood was only able to make two runs past the blockade when in January of 1865 the fall of Fort Fisher deprived Lockwood of a deepwater port to land his cargos. He holed up in Halifax, Canada for a time until word came of Lee's surrender at Appomattox and the end of the war. Lockwood sailed the Col. Lamb back to England and left her in the custody of Fraser, Trenholm and Co. in Liverpool.

The Great Gray Hope

While in Liverpool overseeing the construction of the Col. Lamb, Lockwood had clashed with James Bulloch who was nominally in charge of ship construction and procurement for the Confederate Navy. Perhaps it was a conflict over turf, or the 30% cost overruns Lockwood racked up customizing the Col. Lamb, or both. In any event, Bulloch stated his complaints and then resumed his ship-sourcing activities.

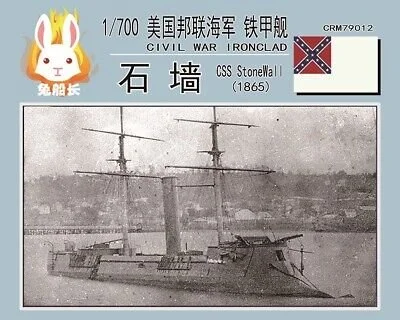

In March of 1863, Bulloch contracted with the French firm of L. Arman for the manufacture of an ocean-going ironclad ship with ramming capability. Union agents in the French port of Bordeaux soon discovered who had ordered the ship and complained loudly to representatives of the French Emperor Napoleon III. At that time, France was deeply involved in Mexico and the Union agents hinted that things could be made very difficult for French forces there if the ironclad was delivered to the Confederates. The Emperor, believing the threats and deciding that discretion was the better part of valor, cancelled the contract with the CSA and sold the ship to the Danish Navy.

Bulloch was not to be stymied so easily, however. He knew that Denmark had just lost a war with Prussia and from his contacts he learned that the Danes were having second thoughts about the purchase. Following the completion of sea trials in the North Sea, the Danes pronounced the ship to be unsuitable for their purposes and directed the selling agent of L. Arman to return it to Bordeaux.

At this point, Bulloch sprang into action: he surreptitiously paid off L. Arman's agent in full, then arranged for Captain T. J. Page of the Confederate Navy and a skeleton crew to board the ship at the dock in Copenhagen. Page fired up the ship's boilers and ran up the CSA Navy ensign. Bulloch himself chose the ship's new name, "a name not inconsistent with her character, and one which will appeal to the feelings and sympathies of those back home." So it was that in the midst of a snowstorm on January 17th, 1865, the CSS Stonewall steamed out of Copenhagen harbor and set out for a secret rendezvous with the CSS City of Richmond to take on a new Confederate crew and a full store of supplies.

News of the Stonewall spread quickly and filled Union Navy commanders with trepidation: a ship like the Stonewall could make short work of the blockade in short order! Her armament consisted of a 300 pounder Armstrong gun mounted in her bow and two 70 pounder Armstrong guns mounted in a casement at her stern. The ship weighed 1,358 tons and was 180 feet long with a 30-foot beam. The Stonewall was covered from stem to stern with iron plates up to 5 inches thick. Page and his crew were shadowed by Union vessels during a long shakedown cruise but were never challenged. The Stonewall and her crew survived a difficult Atlantic crossing and arrived in Havana, Cuba in May of 1865 only to be told that the war had ended. Page surrendered the Stonewall to the Spanish Captain-General in Havana having never fired a shot in anger.

Guns and Glory

* The end of the war found George Trenholm, by then Treasury Secretary of the Confederacy, in prison at Fort Pulaski in Georgia. Most of his assets and properties were confiscated by the American government. Trenholm still had his contacts, though, and managed to somewhat resurrect his shipping and banking interests before he died in 1876. One of Trenholm's banks still exists in Charleston at the corner of East Bay and Broad Street.

* James Bulloch's nephew would later become President Theodore Roosevelt.

* Thomas Lockwood returned to his pre-war occupation captaining a passenger steamer for the Florida Steam Packet line on the Charleston to Jacksonville route.

* Judah Benjamin managed to avoid arrest and slipped away to England where he established a very successful second career as a London barrister. Ever enigmatic, Benjamin burned all of his personal papers and correspondence shortly before his death; a tremendous loss for future historians.

* Caleb Huse eventually became head of a tutoring academy where, in 1882, one of his students was a certain John Pershing who would later command the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe during World War I. The London Armoury Company did not fare as well, forced into bankruptcy in 1866 under the weight of huge amounts of worthless Confederate cotton certificates.

As for the CSS Stonewall, the American government sold it to Japan in 1868 - evidently they wanted it as far away as possible. The Stonewall arrived in time to become the flagship of the new Imperial Japanese Navy.

Renamed "Kotetsu" (literally "Ironclad"), the ship helped Imperial forces soundly defeat the last organized Shogunate rebels at the Battle of Hakodate in May of 1869, thus unifying Japan and demonstrating the value of advanced military technology.

Over 900,000 rifles of all types were imported from overseas by the Union and the Confederacy with the South receiving nearly half. Most Number 1 Enfield rifles were refurbished and sold back to Europe after the war to help pay the union's crushing war debts. Other rifles were brought home as war trophies by decommissioned soldiers and spent the succeeding decades mounted above their fireplaces. It's also likely that the post-war surplus of long and short arms fueled the rapid expansion to the west and helped tame the wild frontier. What's certain is that if these rifles could talk, they'd have quite a tale to tell!

by Steve Levenstein, 2006 ©RLinc