Dixie Doubloons: The Story of the 1861 Confederate Half Dollar

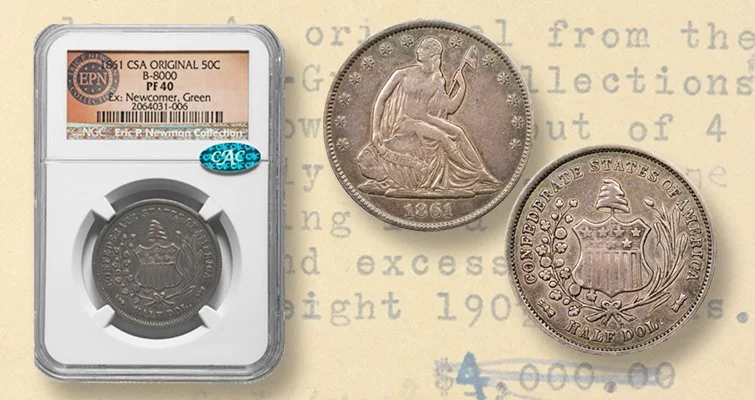

An 1861 Confederate half dollar (one of only four minted) from the legendary Eric P. Newman Collection sold for $960,000 and set a record for a Confederate half dollar at auction

On February 4th, 1861, representatives from seven southern states met in Montgomery, Alabama. The delegates drew up the Constitution of the Confederate States of America and on February 9th elected Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as the first President of the CSA. A new nation was born, sovereign in fact but sorely lacking in the trappings of sovereignty. It was a simple thing to run the Stars and Bars up the flagpole, but there were other more problematic issues of identity the leadership of the Confederacy had to contend with.

The Union had none of these concerns, of course, since the southern states had seceded from them and not the reverse. The CSA had to start from scratch as a newly minted nation and time was of the essence. It quickly became apparent that President Lincoln and the Union were not going to let the South go without a fight, regardless of Jefferson Davis' plea that "All we ask is to be let alone".

Confederate military doctrine stated that if the struggle between North and South should escalate to all-out war, their armed forces would assume a defensive posture and fight a war of attrition. The theory was that the northern public, having no great cause to fight for, would soon tire of the privations war would surely bring and pressure their leaders to settle with the Confederacy. In essence, the plan was not to win the war, but not to lose it.

Minding the Mint

The Confederate brain trust couldn't estimate how long this would take, of course, and to paraphrase Lincoln: a house standing alone cannot stand for long. The Confederacy's diplomatic efforts focused on at least maintaining trade with Britain and France, at best drawing them into the war to protect their textile industries which processed Southern cotton.

Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, known as "the brains of the Confederacy", knew that he had to present the CSA as a viable nation and not just a mere collection of states temporarily united by the need for group self-defense. One way that nations establish an identity at home and abroad is through the use of a distinctive national currency, yet the Confederacy had no currency of its own. It was easy enough to print bank notes and stamps (and printed they were, in abundance), but coinage in precious metal carried, literally, much more weight.

Benjamin was from Louisiana and had represented his state as a Senator in Washington so he was fully aware of the U.S. Mint in New Orleans and how it could be utilized to further the interests of the Confederacy.

New Orleans Mint, opened 1838

The New Orleans Mint was the brainchild of Andrew Jackson, seventh president of the United States. Jackson was a native of North Carolina who later became Tennessee's first congressman. An advocate of economic decentralization and expansion of the United States west of the Mississippi, Jackson was also an opponent of the powerful eastern banking magnates. Establishing a series of branch mints would dilute the influence of the Philadelphia Mint and at the same time help supply the western states and territories with coinage to fuel their economic expansion. The wisdom of this policy was proved when massive amounts of gold bullion began to flow from the California goldfields and the rich silver mines of Nevada.

So it was that in 1835, President Jackson oversaw an Act of Congress authorizing the establishment of a branch mint at the important port of New Orleans (as well as Charlotte, North Carolina, and Dahlonega, Georgia). The mint was to be built on a 1.6 acre park on the edge of the French Quarter (coincidentally, this was the exact spot where "Old Hickory" had inspected his troops prior to the battle of New Orleans in 1815).

Construction of the mint took 3 years and cost over $300,000, a considerable sum in those days. The fortress-like edifice was so well constructed that 120 years later at the height of the Cold War it was designated the city's premier fallout shelter. The mint produced a wide variety of gold and silver coins on hand-operated screw presses until 1845 when they were replaced by much more efficient steam presses. Each coin bore a distinctive "O" mintmark designating its origin. Nearly $70 million in coinage had jingled out of the mint by January 26th, 1861 when Louisiana seceded from the Union. One of the first acts of the state legislature was to order the state militia to secure control of the mint and its $5 million stock of gold and silver coins and bullion.

Coin of the Realms

In the mid-nineteenth century, a dollar was an average day's pay for many workingmen and silver dollars weren't commonly used in everyday transactions. The silver half dollar was the workhorse, playing the role that the $20 note performs in today's economy.

Chief Coiner Dr. B. F. Taylor and his staff at the New Orleans Mint had overseen production of 330,000 silver 1861 half dollars when Louisiana state troops marched through the doors on January 31st and announced a "change in management".

Production continued without a hitch, however, and records show that a further 1,240,000 silver halves were struck under the supervision of state officials. On February 28th, the Confederate central government assumed control of the newly renamed Confederate State Mint and proceeded to strike an additional 962,633 half dollars, bringing the grand total of 1861-O silver halves minted to 2,532,633.

This was all well and good except for the fact that all of the coins were struck with the same dies, making them indistinguishable from one another regardless of which government minted them. They shared the date of 1861, the "O" mintmark, and of course the Seated Liberty and Federal Eagle designs that had graced United States coins for decades.

Christopher Gustavus Memminger was the Confederate Treasury Secretary at the time. Although he surely welcomed the outpouring of new coins, he was surely less pleased by the "Yankee" motifs and "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA" legends they sported. A revised design would help boost the self-esteem of their infant nation and symbolize the permanence of the Confederacy. It would also fulfill Secretary of State Benjamin's desire to show a "calling card" to fence-sitting foreign countries whose support the Confederacy desperately needed.

Accordingly, in early April of 1861 Memminger issued tenders for a new Half Dollar design and received several responses. First to be approved was a new reverse design submitted by New Orleans engraver and die-sinker A.H.M. Patterson. The motif was distinctively different from the Eagle reverse used by and associated with the Union, and drew upon traditional heraldic coin and medal designs.

It featured a shield centered between curving boughs of cotton and sugar cane, mainstays of southern agriculture. The upper portion of the shield contained seven stars representing the seven seceding states who originally founded the Confederacy: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. Below the stars were seven vertical raised stripes. Rising above the shield was a Liberty Cap on a pole. The legends "CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA" and "HALF DOL." filled out the area between the cereal wreaths and the rim. Considered on its own, it was a handsome and well-balanced design.

The problem was, coins have two sides. We can assume that Patterson was working on a new design for the obverse or was planning to do so, however there are no records to confirm this. Retaining the Seated Liberty obverse would have presented a number of problems:

· As the Civil War progressed, it's certain that a "half Yankee" coin would have been disparaged and rejected by the hard-pressed citizens of the Confederacy.

· Such a coin wouldn't pass the litmus test of being a true symbol of sovereignty. Instead, the half & half design indicated expediency and thus would only frustrate Benjamin's need to impress the CSA's overseas trading partners. As confirmation of Benjamin's state of mind on the issue of a national currency, CSA government records show that on January 22nd, 1863, he proposed the minting of a $5 denomination gold coin. The "Cavalier", as it was to be called, would have the same value as the British gold sovereign. Also planned were $10 and $20 gold pieces (referred to as "Double Cavaliers" and "Quadruple Cavaliers" respectively) which were intended to simplify and facilitate trade with the Confederacy's major cotton purchasers.

· The two halves of the coin simply didn't match. The Federal obverse featured a seated Lady Liberty holding a pole with a Liberty Cap on the end. The Liberty Cap motif is prominently featured on the Patterson reverse. It would be very unusual to have the same design feature on both sides of a coin. The Seated Liberty obverse also featured thirteen stars representing the original thirteen colonies. In early 1861, the only Confederate states represented by any of those stars were South Carolina and Georgia. It's highly unlikely that doing a time of war, the people of the South would put up with having symbols of enemy Northern states on their coins! Although it is true that the Confederacy did eventually expand from seven states to thirteen, the thirteenth state (Kentucky) did not secede until November of 1861.

Patterson completed his reverse design and prepared a die, which he brought to Taylor for approval. Taylor noticed that the reverse would strike a coin with high relief and that this could cause the planchets to stick to the dies after being struck, so he ordered the striking of four proof trial pieces using Patterson's reverse die and a standard Seated Liberty obverse die. There were problems fitting the new reverse die to the coin press, so the four trial pieces were hand struck on the old screw press.

Taylor, being Chief Coiner, kept one of the coins for himself. Two others were given to a Dr. E. Ames of New Orleans and Prof. Riddell (or Biddle) of the University of Louisiana. Both Ames and Riddell were prominent citizens; Riddell was a former mint employee. The fourth coin was sent to Treasury Secretary Memminger who in turn presented it to President Davis.

In the natural course of events, Patterson would have completed a new obverse die and assuming the design was approved, the new half dollar would have then gone into production. It was not to be. As was the case with so many of the Confederacy's plans, however, they were frustrated by time and events: too little time and too many adverse events.

By the spring of 1861 it became obvious to both sides that the war was going to last years, not months as originally hoped. The price of precious metals (always a safe harbor in difficult times) rose beyond the face values of the coins they were used in. Coinage of all kinds vanished from daily use. Striking new silver coins for circulation would be an exercise in futility as they would only be hoarded by the public. This is assuming there was any bullion still available... the coin presses had been stamping out Seated Liberty halves without pause, regardless of the fact that new designs were being contemplated.

By the end of April silver supplies had been exhausted. Between the Union naval blockade and the constricting front lines of the war on land, there was no way to supply the Mint with more bullion. Memminger could read the writing on the wall and ordered minting operations suspended on April 30th, 1861. Printed paper notes and fractional currency would have to sustain the pulse of the nation's economy.

One year later, New Orleans fell to Farragut's Union naval forces. The Mint was seized (becoming the headquarters of the Union garrison) and Benjamin's dream of a Confederate national coinage was dashed.

The Final Four

Against all odds, the four trial Confederate half dollars have managed to survive to this day. The Ames and Riddell coins now reside in the hands of private collectors. The coin presented to Secretary Memminger has a much more colorful history. Jefferson Davis kept the coin Memminger gave him and used it as a pocket piece. In fact, he considered it to be his "lucky coin".

Shortly before his surrender to Union forces on May 10th, 1865 at Irwinville, Georgia, Davis gave the coin and his other valuables to his wife Varina for safekeeping. It was the last he ever saw of it. When a New York coin dealer named J. W. Scott wrote to Davis years later asking about the coin, Davis replied personally:

Beauvoir, P. O.

Harrison Co., Miss.

Sir:

I had a Confederate coin. It was in my wife's trunk when it was rifled by the Federal officers on board the prison ship on which she was detained at Hampton Roads before and after my confinement in Fortress Monroe. The coin, some medals and other valuables were stolen at that time. Whether the coin be the same which has been offered to you as a duplicate, I cannot say. It is, however, not true, as published, that it is now in my possession.

Regretting that I cannot give you more exact information on the particular subject of your enquiry, I remain,

Respectfully, Jefferson Davis

Incredibly, one of the four original Confederate Half Dollars was discovered in circulation! Some lucky person in 1890's New York must have been quite surprised to find a Confederate coin in their pocket change. It's very likely, though impossible to prove, that this was Jefferson Davis's stolen lucky coin. In 2003 the half dollar was sold at auction for an unprecedented $550,000.

The coin kept by Dr. Taylor, along with Patterson's reverse die, languished in his safety deposit box until 1879 when Taylor read an article written by E. Mason Jr., a Philadelphia numismatist and coin dealer, and subsequently contacted him. Mason bought the coin and die from Taylor, then resold them to J. W. Scott (prompting Scott to write to Jefferson Davis) for $310. Scott sold the coin for $870 in 1882 and it now resides in the collection of the American Numismatic Society in New York.

Scott kept the die, however, cleaning and polishing it with the intention of striking new coins. He decided to test the die by striking 500 white metal (probably tin) tokens. He paired the Confederate reverse die with a homemade obverse die advertising his business:

"4 ORIGINALS STRUCK BY ORDER OF C.S.A. IN NEW ORLEANS 1861 ******* REV. SAME AS U.S. (FROM ORIGINAL DIE SCOTT)"

Encouraged by the strength of the die, Scott moved on to the next phase of his plan. He acquired 500 actual 1861-O half dollars, a daunting proposition even though just 18 years had passed since they were minted. Many of the coins Scott used for his restrikes were circulated and showed significant wear. He began striking coins using the Confederate reverse die but discovered on inspection that some areas of the Federal design were still visible. Even worse, the Confederate die broke and had to be secured within a steel collar. Scott wasn't about to be stymied after having come this far. He proceeded to "shave" the Eagle design off of the remaining coins, then resumed striking them with the Confederate die. The Seated Liberty design on all of Scott's restrikes appears somewhat flattened and distorted as a consequence of the stamping process, differentiating them from the four original Confederate trial pieces.

Scott's tokens and restrikes trade actively at coin auctions today. The tin tokens are worth up to $3500 each while the restrikes can bring as much as $8500 depending on condition.

Coin-federacy

The intense interest these coins have garnered is not surprising given the lasting impression the Civil War has left on the American psyche. The coins themselves, with their Union obverses and Confederate reverses, display the War in microcosm.

It can also be said that the history of the 1861 Confederate Half Dollar mirrors the story of the Confederacy: grand plans, lofty hopes, and lingering questions of what might have been. These coins were intended to be the first of many, proud symbols of a new nation. Instead, they are among the last remaining vestiges of the Lost Cause.

by Steve Levenstein, 2005 ©RLinc